Keep an eye out for these new releases.

By Lindsay Baker27th October 2020From candid memoir and unsettling dystopia to the Booker-shortlisted novels, Lindsay Baker rounds up BBC Culture’s reading recommendations.T

The New Wilderness by Diane Cook

Living in an overpopulated, polluted metropolis, Bea realises she and her daughter cannot stay in the city, and so join a group of volunteers to take part in an extreme experiment. The group must settle in the Wilderness State, a huge, untamed expanse of land that has never been inhabited by humankind, until now. Dystopian novel The New Wilderness has been shortlisted for the Booker. The Booker Prize describes it as: “At once a blazing lament of our contempt for nature… and what it means to be human, The New Wildernessis an extraordinary, compelling novel for our times.”

Oneworld

This Mournable Body by Tsitsi Dangarembga

Tambudzai is a young woman attempting to make a life for herself in downtown Harare. Tsitsi Dangarembga’s latest novel, a sequel to her 1988 classic Nervous Conditions, has been shortlisted for the Booker. It follows Tambudzai’s progress, as she faces setback after setback and as she finally reaches breaking point. It is a “tense and psychologically charged novel” according to the Booker Prize, and The Guardian says: “Three decades on, Dangarembga has written another classic.”

Faber

Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi

As a young woman, Tara left her arranged marriage to join an ashram, then took an artist lover, rebelling against convention and social expectation. Now she is an old woman, and Burnt Sugar untangles her complex relationship with her daughter. The Telegraph describes the novel as “a corrosive, compulsive debut”. The novel has been shortlisted for the Booker Prize: “Sharp as a blade and laced with caustic wit, Avni Doshi tests the limits of what we can know for certain about those we are closest to, and by extension, about ourselves.”

Hamish Hamilton

The Shadow King by Maaza Mengiste

Set during Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, The Shadow King tells the story of the recently orphaned Hirut. She begins the novel working as a servant, and gradually transforms herself into a proud warrior. The New York Times describes the novel as “lyrical” and “remarkable”, and Hirut as an “indelible and compelling hero”. The Shadow King has been shortlisted for the Booker Prize, whose judges praised it as “a captivating exploration of female power”.

Canongate

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart

The debut novel by Douglas Stuart draws on his own childhood in 1980s Glasgow. Shuggie is the youngest of three children, and Agnes is his alcoholic mother. This widely acclaimed, Booker-nominated story centres on the relationship between mother and son. “Douglas Stuart’s startling Glasgow-set debut novel creates a world of poverty and suffering offset by pure, heart-filling, love,” said The Scotsman review. “It’s a novel that deserves, and will surely often get, a second reading”.

Picador

Mayflies by Andrew O’Hagan

Andrew O’Hagan’s latest novel is inspired by real events, and the friendship between two men, Jimmy and Tully. In a small Scottish town in the 1980s, the two teenagers bond over their love of music and films, and a rebellious teen spirit. They share a magical, euphoric weekend in Manchester. Thirty years later, and Tully has some news. The Telegraph calls Mayflies “a delightful nostalgia trip of enduring friendship.” The Times says: “A joyful, warm and heart-filling tribute to the million-petalled flower of male friendship.”

Faber

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

Piranesi is, according to inews, “The most curious confection… blending elements of mythology and fantasy, with nods along the way to CS Lewis and Tolkien… [it has a] genuinely moving climax that throws open the doors of the halls in more ways than one.” Its author Susanna Clarke is known for her 2004 debut novel Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, an award-winning alternative history. Piranesi has been much lauded, and described by critics as “brilliantly singular” and “utterly otherworldly”.

Bloomsbury

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

The Vanishing Half is a story about the way that identity is formed, and tells of identical, light-skinned twin sisters, born in the Jim Crow South, who run away from home as teenagers. The girls then go their very separate ways. Desiree returns home 14 years later, while her sister Stella has seemingly vanished, having taken on a white persona. The follow-up to Bennett’s 2016 debut The Mothers, The Vanishing Half has been widely acclaimed. As The New York Times puts it: “Bennett balances the literary demands of dynamic characterisation with the historical and social realities of her subject matter.”

Dialogue Books

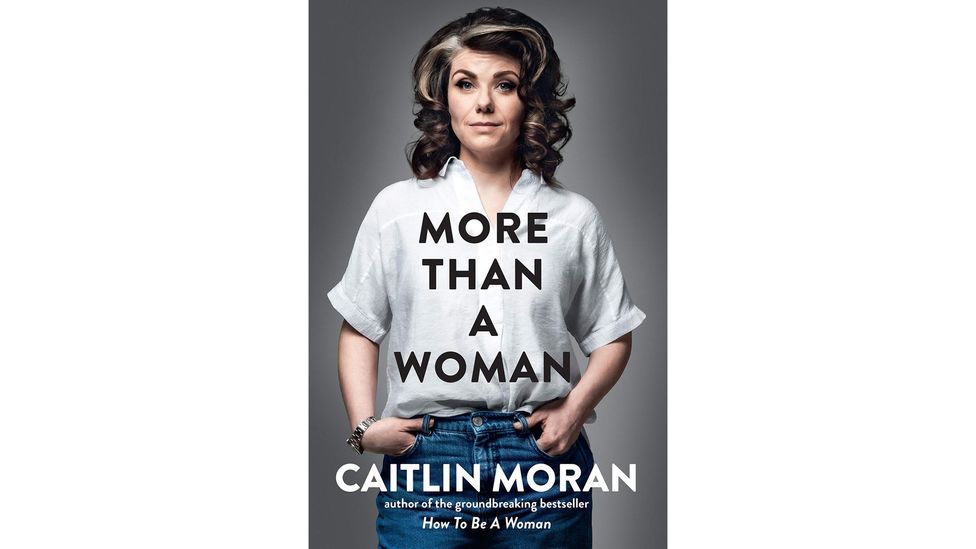

More Than a Woman by Caitlin Moran

The British journalist and author Caitlin Moran is already known for her funny, smart observations about girlhood and womanhood. Her 2011 book How to Be a Woman was hugely influential; her latest, More Than a Woman, is a reflection on what it means to be a woman in middle age. Themes include multi-tasking, caring for teenaged children, gender stereotypes and long-term relationships. The Observer says: “Moran proves herself, once more, a sage guide in the joys, as well as the difficult bits, of being a woman – of being a partner, mother, friend and feminist.”

Ebury Press

The First Woman by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi

Growing up in a small Ugandan village, Kirabo is surrounded by powerful women, all of whom want her to conform. As she approaches womanhood, though, the headstrong Kirabo becomes rebellious. Set against the backdrop of a country transformed by dictatorship, The First Woman blends modern feminism with ancient Ugandan folklore. “Makumbi balances heartbreak with humour,” says The Telegraph. “The novel is also a discourse on power (whether political, social or sexual), but executed with a beautifully light touch.”

Simon and Schuster

Earthlings by Sayaka Murata

Convenience Store Woman, Sayaka Murata’s previous novel, was a bestseller and a critical hit. The follow-up, Earthlings, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori, has at its centre a similarly neuro-diverse heroine. The protagonist of Murata’s new novel, Natsuki, is detached, having suffered a traumatic childhood, and struggles with the expectations placed on her. She is “vividly drawn”, according to The Observer. “Natsuki makes for a compelling narrator, and Earthlings is a frequently disturbing but pacy read, with its own off-key humour.”

Granta

Daddy by Emma Cline

Emma Cline’s first novel, The Girls, was a critically acclaimed triumph, and now her collection of short stories, Daddy, has also been well received. The stories explore the darker side of human experience and focus on the power dynamics between men and woman, parents and children – and the tensions between past and present. “Cline is particularly good at locking in the witty detail that speaks volumes,” says The Times. “These expertly constructed stories withhold key information... the pleasures here lie in an appreciation of Cline’s skilful and absorbing craft.”

Chatto & Windus

Jack by Marilynne Robinson

Pulitzer-winning Marilynne Robinson has written a fourth novel in her acclaimed Gilead series. It tells the story of a much-loved son of a Presbyterian minister who in segregated St Louis falls in love with Della, an African-American school teacher. Love, race and the mores of the mid-West are central themes in a book described by The Guardian as “radiant and visionary”.

Little, Brown

Poor by Caleb Femi

In Poor, Caleb Femi blends poetry and photography to look at the hopes, dreams and tribulations of young black boys in 21st-Century south London. The poetry explores, among other themes, the past and how to make sense of it, and Femi was the first Young People’s Laureate for London in 2016. “An urban romantic with a powerful understanding of why spoken word matters,” according to Dazed.

Penguin

That Old Country Music by Kevin Barry

In his third collection of short stories, Kevin Barry portrays an Ireland in transition, and also a country where tradition and myth still endure. His funny, dark vision has been much acclaimed, and That Old Country Music has been described by The Times as “one of the best collections you’ll read this year. The master short story teller turns messy emotions into riveting tales of wounded Irish folk”.

Canongate

I Am Not Your Baby Mother by Candice Brathwaite

Described by the London Evening Standard as “an observant and timely guide”, I Am Not Your Baby Mother by blogger Candice Brathwaite is a memoir and a manifesto about black motherhood. The book has become a bestseller and has been widely praised. “Written in her brilliantly witty manner, this book is every black British woman’s motherhood manual,” said Refinery 29.

Baby mother

Must I Go by Yiyun Li

Lilia Liska has raised five children and outlived three husbands, and now she turns her attention to the diary of a man with whom she once had an affair. In the process she tells her own, rather different, version of events, revealing the secrets of her past. The award-winning fiction of Yiyun Li has been widely celebrated. “Li has crafted an epic story of a life full of regret, but also of hope and perseverance and the importance of passing down our legacies,” according to Vulture.

Yiyun li

Rodham by Curtis Sittenfeld

What would have happened if Hillary Rodham had never married Bill Clinton? Sittenfeld answers this question with Rodham, a novel that weaves an imagined tale into real historical events. In it, Hillary blazes her own trail, and on the way encounters compromise, ambivalence and exhilaration, explored compellingly by Sittenfeld. “Her ear is attuned to inconvenient truths and double standards, particularly misogyny in America. She specialises in awkward encounters and surprise shifts in power,” says the New Statesman.

Rodham crop

How Much of These Hills is Gold by C Pam Zhang

Set against the backdrop of the American gold rush, How Much of These Hills is Gold focuses on two orphaned siblings are on the run, trying to find a home. Along the way they encounter hardship but also glimpses of a different future. Full of Chinese symbolism, this debut novel is an adventure story that explores the themes of memory, family and belonging. The New York Times describes it as a “haunting, arresting” read. “By journey’s end, you’re enriched and enlightened by the lives you have witnessed.”

Riverhead

American Poison by Eduardo Porter

American Poison: How Racial Hostility Destroyed our Promise is a wide-reaching examination of US racism. Porter explores how this national pathology has stunted the nation’s development and the growth of the institutions needed for a healthy, cohesive society – including labour, education, health and welfare. But it also points the way towards hope and a new understanding of racial identity. “Learned, well-written… a bracing wake-up call,” says the New York Times Book Review.

Penguin Random House

You People by Nikita Lalwani

Going behind the scenes of a London pizza restaurant, You People centres around Tulu, the pizzeria’s proprietor. A Robin Hood character, he aims to help anyone in need, but when his guidance leads into dangerous territory, the characters are faced with a difficult moral choice. “This is a moving, authentic, humane novel,” says the Guardian, “which raises fundamental questions about what it means to be kind in an unkind world.”

Viking

Rainbow Milk by Paul Mendez

New writer Paul Mendez explores sexuality, race, class and religion across generations and cultures in his semi-autobiographical debut novel Rainbow Milk. In this coming-of-age story, protagonist Jesse McCarthy grapples with his identity and upbringing as a Jehovah’s Witness in a disempowered region of the UK, as well as the complex legacy of the Windrush generation. “Exhilarating, a bravura piece of writing… Mendez looks set to shake up the literary establishment in the most thrilling way,” says the i newspaper.

Hachette

Wow, No Thank You by Samantha Irby

“The bawdiest humour, the biggest heart,” is how the Irish Times describes Samantha Irby’s collection of essays, Wow, No Thank You. The author of the best-selling We Are Never Meeting in Real Life draws unflinchingly on her own life. Having left Chicago and her job as a vet’s receptionist, she has moved to California where she lives with her wife. “Wildly, seditiously funny,” says the New York Times, “this is her voice: deadpan, confiding, companionable.”

Penguin Random House

A Children’s Bible by Lydia Millet

“A blistering classic,” is how the Washington Post describes Pulitzer finalist Lydia Millet’s new novel A Children’s Bible. A modern retelling of Noah’s Ark, Millet’s tale is of a group of idle, wealthy friends and their feral children. The families have rented a mansion for the summer, and then a massive hurricane hits. It is, says Vulture, “that rare and precious thing: a funny dystopia”.

WW Norton and Co

If I Had Your Face by Frances Cha

Set in contemporary Seoul, this debut novel follows the lives of four young women as they set about making lives for themselves in a world where the odds are stacked against them. As the women navigate various challenges, their tentative bond evolves. People says: “An enthralling tale about the weight of old traumas, economic disparity and the restoring power of friendship.”

Viking

The Glass Hotel by Emily St John Mandel

A story about crisis, survival and the search for meaning in our lives, The Glass Hotel explores two intersecting but seemingly separate events – the collapse of a huge Ponzi scheme, and the strange disappearance of a woman from a ship at sea. Mandel’s award-winning dystopian novel Station Eleven was widely acclaimed, and her latest offering has been similarly well received. The Atlantic describes the novel as “deeply imagined, philosophically profound”.

Knopf

Redhead by the Side of the Road by Anne Tyler

Anne Tyler’s books are perfect comfort reading, and her new novel Redhead by the Side of the Road is no exception. The novel explores the heart and mind of a man who is struggling to negotiate unexpected events in his life. Full of her usual compassion, empathy and joyfulness, it is classic Tyler, and has been highly praised. “If ever there was a perfect time for a new Anne Tyler novel, it’s now,” says the Wall Street Journal. “Very funny – one of Tyler’s best yet.”

Penguin Random House

Collected Stories by Lorrie Moore

Hailed as one of the most significant voices in US fiction, Moore is a master of the short story. Now the complete stories – smart, witty and beautifully crafted – are gathered together, including three new and previously unpublished in book form. Her stories, says the New York Review of Books, “no matter how often you read them, are an endlessly rich and renewing source of pleasure and inspiration”.

Faber and Faber

Sharks in the Time of Saviours by Kawai Strong Washburn

Intertwining Hawaiian folklore with the reality of the modern-day US, Sharks in the Time of Saviours is a debut novel by Kawai Strong Washburn. The characters are depicted in a contemporary, yet also mystical, version of Hawaii. “This may be his debut,” says The New York Times Book Review, “but he proves himself an old hand at dissecting the ways in which places — our connections to them, our disconnections from them — break us and remake us.” (Credit: Canongate)

Canongate

Weather by Jenny Offill

A series of episodic vignettes, the widely acclaimed novel Weather is narrated by librarian Lizzie, who speaks with frankness about her daily preoccupations and ordinary anxieties. These include worries about her troubled mother, her recovering-addict brother – and the climate emergency. “Weather achieves a rare triumph… it’s an uncannily realistic portrait of what it’s like to be alive right now,” says the Telegraph. In its musings, jokes, and snatches of memory, the book “zooms from the micro to the macro”, according to the New Statesman. “Weather captures the anxiety and absurdity of the 21st Century.”

Weather

Real Life by Brandon Taylor

The Booker nominated Real Life tells the coming-of-age story of Wallace, who is studying for a biochemistry degree but is at odds with the midwestern university town he finds himself in. A shy young man from Alabama, he has left his family behind – but not his troubling childhood memories. Then come confrontations with colleagues and a surprise encounter with a classmate. “Brandon Taylor emerges as a powerhouse with this artful debut,” says Newsweek. “In tender, intimate and distinctive writing, Taylor explores race, sexuality and desire with a cast of unforgettable characters.”

Real Life

Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid

When 25-year-old Emira Tucker is wrongly accused of kidnapping the child in her care, a series of events unfolds that raises questions about class, race, parenthood and morality. Yet this debut novel is written with a light touch, and makes for a witty, if uncomfortable, social satire. “Charming, authentic and every bit as entertaining as it is calmly, intelligently damning,” was the Observer’s verdict. The Atlantic, meanwhile, describes Such a Fun Age as “a funny, fast-paced social satire about privilege in America”.

Such a Fun Age

Motherwell: A Girlhood by Deborah Orr

The acclaimed journalist Deborah Orr died in November 2019, and earlier this year her remarkable and unflinching book Motherwell was published. In this candid and occasionally humorous memoir, Orr recalls her 1970s, working-class upbringing in Scotland, and her complicated relationship with her mother. Motherwell is, says Andrew O’Hagan in the Guardian, “a masterpiece of self-exploration”, and its “greatness lies mainly in the psychological dimension, in the vivid portrait of her parents’ narcissism and the just-as-vivid portrait of her own”. As the Scotsman observes: “It is disconcertingly honest and self-revealing. You are unlikely to forget it.”

Motherwell

Apeirogon by Colum McCann

Two men, one Israeli and one Palestinian, had a daughter killed in in the conflict. Then they become friends. Apeirogon by Colum McCann is based on the true story of this friendship, and has been widely praised. It is “a masterpiece” and “the kind of book that comes along only once in a generation” says the Observer. “Brilliant... powerful and prismatic,” says the New York Times. “Apeirogon is an empathy engine, utterly collapsing the gulf between teller and listener... It achieves its aim by merging acts of imagination and extrapolation with historical fact.” It is a “profoundly human” novel, says BBC Culture.

Apeirogon

Cleanness by Garth Greenwell

Greenwell’s second novel Cleanness follows his acclaimed debut What Belongs to You. He continues the story of a US teacher living in Bulgaria, and explores his memories and sexual encounters through a disordered narrative. The Washington Post calls the novel “quite simply, a work of genius that will change the way you understand the world and your place in it.” The New York Times, meanwhile, says: “[Greenwell's] writing about sex is altogether scorching... Greenwell has an uncanny gift, one that comes along rarely”.

Cleanness

Hood Feminism by Mikki Kendall

While dissecting white feminism, this book also focusses on productive solutions and a hopeful approach. Refinery 29 describes Hood Feminism as “blistering... A fresh new and necessary black voice in feminist literature”. The book is a “much-needed reality check”, says inews: “The author has a canny ability to take heavy, complex subjects and translate them into concrete, sound arguments, offering practical resolutions”.

Hood Feminism

The Mirror and the Light by Hilary Mantel

The much-anticipated finale of Mantel’s trilogy about King Henry VIII’s right-hand-man Thomas Cromwell has been well received. Mantel’s Cromwell is a complex, consummate player, more powerful in many ways than the king himself. The Mirror and the Light charts his downfall, and as The Atlantic points out, “Cromwell’s charisma is never allowed to dissipate”. The Guardian hails the book as a “masterpiece” and as “a novel of epic proportions [that is] every bit as thrilling, propulsive, darkly comic and stupendously intelligent as its predecessors...The trilogy is complete and it is magnificent”.

Mirror and Light

House of Glass by Hadley Freeman

In House of Glass the journalist Hadley Freeman uncovers her family’s secrets, focussing on the life story of her grandmother, who escaped the horrors of Europe during World War Two to live in the US, as well as the contrasting lives of her great uncles. “It is the product of 20 years of research, and it amounts, by sheer cumulation of detail, to a near-perfect study of Jewish identity – of Jewish being – in the 20th Century,” says the Telegraph. Or, as Kirkus puts it: “Frightening, inspiring, and cautionary in equal measure”.

House of Glass

Actress by Anne Enright

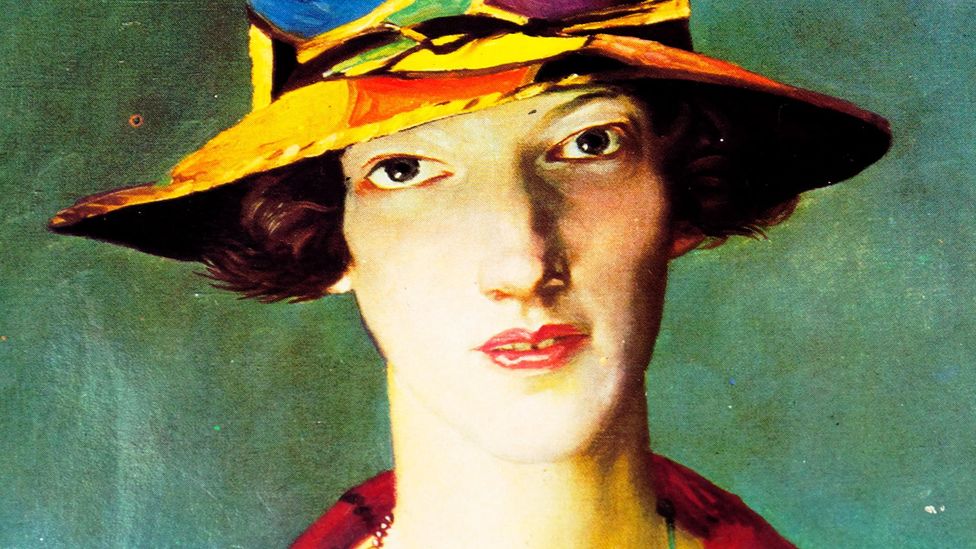

Irish author Anne Enright’s new novel Actress has been longlisted for the Women’s Fiction Prize, and is a tale of fame, power, and a daughter’s quest to understand her mother. It is, says the Washington Post, “brilliant… the deceptively casual flow of her stories belies their craft, a profound intelligence sealed invisibly behind life’s mirror”. The Observer also praises the author, who has previously won the Booker: “Enright triumphs as a chameleon: memoirist, journalist, critic, daughter – her emotional intelligence knows no bounds.”

Actress

Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell

Maggie O’Farrell’s latest novel was inspired by the true story of Shakespeare’s only son, Hamnet, who died aged 11. “Hamnet is a novel apart. It shares the page-turning verve of its predecessors,” says the Observer, and has “the power of letting a story appear to tell itself”. The Sunday Times describes Hamnet as “powerful” and “an intense poetic exploration of parental grief”.

Hamnett

Where the Wild Ladies Are by Matsuda Aoko

This collection of stories, translated by Polly Barton, are inspired by traditional Japanese mythology, but with a feminist twist and a modern setting. The stories feature demons and ghosts, skeletons and spirits, but the original tales are all imaginatively up-ended by Aoko, and told from a contemporary, female perspective. Where the Wild Ladies Are is, says the Guardian, “funny, beautiful, surreal and relatable – this is a phenomenal book”.

Wild Ladies

The Death of Comrade President by Alain Mabanckou

Alain Mabanckou’s Black Moses was longlisted for the 2017 Booker Prize. Now his new book The Death of Comrade President, translated by Helen Stevenson, has also been well received. It is a coming-of-age tale set in the 1970s in Pointe-Noire in the Republic of Congo, where young Michel is negotiating everyday life, until the brutal murder of the president. Bookshybooks says: “Starting as a tender portrait of an ordinary Congolese family, Alain Mabanckou quickly expands the scope of his story into a powerful examination of colonialism, decolonisation and the dead ends of the African continent.”

Comrade

Minor Feelings by Cathy Park Hong

The poet Cathy Park Hong examines Asian-American identity in Minor Feelings. “It bled a dormant discomfort out of me with surgical precision,” writes Jia Tolentino in the New Yorker of the collection of essays that explores identity, race and neoliberalism. “Hong is writing in agonised pursuit of a liberation that doesn’t look white – a new sound, a new affect, a new consciousness – and the result feels like what she was waiting for.”

Minor Feelings

A Long Petal of the Sea by Isabel Allende

A ship takes 2,000 refugees from the Spanish Civil War to Chile in 1939. “This exodus is the basis for Allende’s riveting new historic saga, which has echoes in today’s global refugee crises – and parallels to Allende’s own life,” says Jane Ciabattari on BBC Culture. Translated from the Spanish by Nick Caistor and Amanda Hopkinson, Allende’s latest novel is, according to the Telegraph, “a gripping tale of love in exile”.

Long Petal of the Sea

Our House is on Fire by Greta Thunberg et al

This family account of Greta Thunberg’s Asperger’s diagnosis has been hailed as a must-read environmental message of hope. Our House is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis is co-authored by Thunberg’s mother Malena Ernman, who is the primary narrator, her father Svante, and her sister Beata. It is, “an urgent, lucid, courageous account,” says David Mitchell in the Guardian. “Everyone with an interest in the future of the planet should read this book. It is a clear-headed diagnosis. It is a glimpse of a saner world. It is fertile with hope.”

House of Fire

And if you liked this story, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

SIMILAR ARTICLES

By Hephzibah Anderson19th August 2020What is revealed by the early manuscripts of classic novels? From the works of Wilde and Woolf to Fitzgerald and Proust, Hephzibah Anderson investigates.W

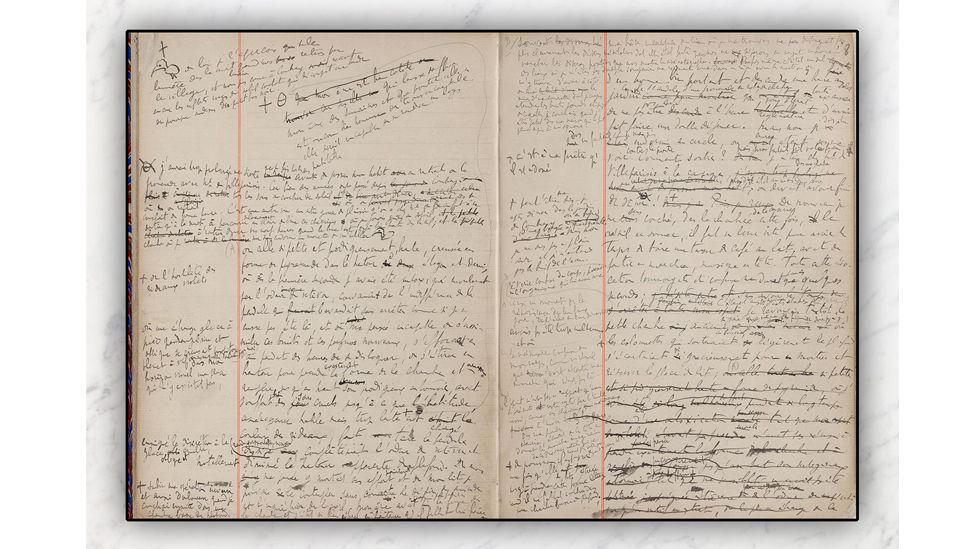

Writers who find themselves mired in procrastination would do well to take a page from Marcel Proust’s most famous book. Specifically, a page from In Search of Lost Time in manuscript form. Nothing more powerfully illustrates the truth of that creative-writing-class maxim, ‘writing is rewriting’, than the liberally crossed-out, lavishly annotated, occasionally doodled-upon notebooks in which Proust composed his seminal, seven-volume text.

More like this:

While their faded ink and age-dappled paper evoke physical fragility, what they showcase is a robust, almost aggressive determination. This is the heavy lifting of literary endeavour made manifest; there is no preciousness here, nothing is sacred. However much Proust doubted himself – and he doubted his chosen art form, too – he pressed on with a monumental task that would occupy him for the rest of his life. As for that iconic morsel of memory-laden cake, the madeleine, it started out as a slice of toast and a cup of tea.

The notebooks in which Proust hand-wrote his masterpiece In Search of Lost Time are full of the author’s revealing notes (Credit: SP Books)

The manuscripts of literary works-in-progress fascinate on many levels, from the flush-faced thrill of spying on something intensely private and the visceral delight of knowing that a legendary author’s hand rested on the paper before you, to the light that such early drafts shed on authorial methodology and intent. Sometimes, the very essence of what a writer is trying to express seems to hover tantalisingly in the gap between a word deleted and another added in its place.

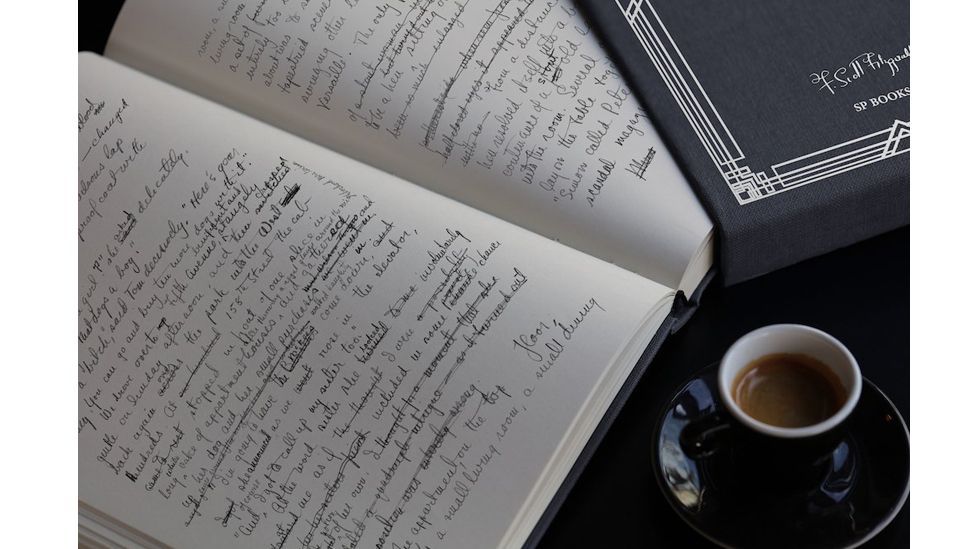

Elsewhere, discombobulating differences can inspire in the reader fresh takes on even the most well-thumbed texts. Openings and endings turn out to have been quite different in their earliest renderings, and beloved characters are to be found taking their first steps bearing very different names. For instance, Gone with the Wind’s Scarlett O’Hara was originally called Pansy, Arthur Conan Doyle’s deerstalker-wearing detective answered to Sherrinford Hope, and The Great Gatsby’s Daisy and Nick were Ada and Dud.

The original manuscript of The Great Gatsby reveals intriguing details about Fitzgerald’s intent and method (Credit: SP Books)

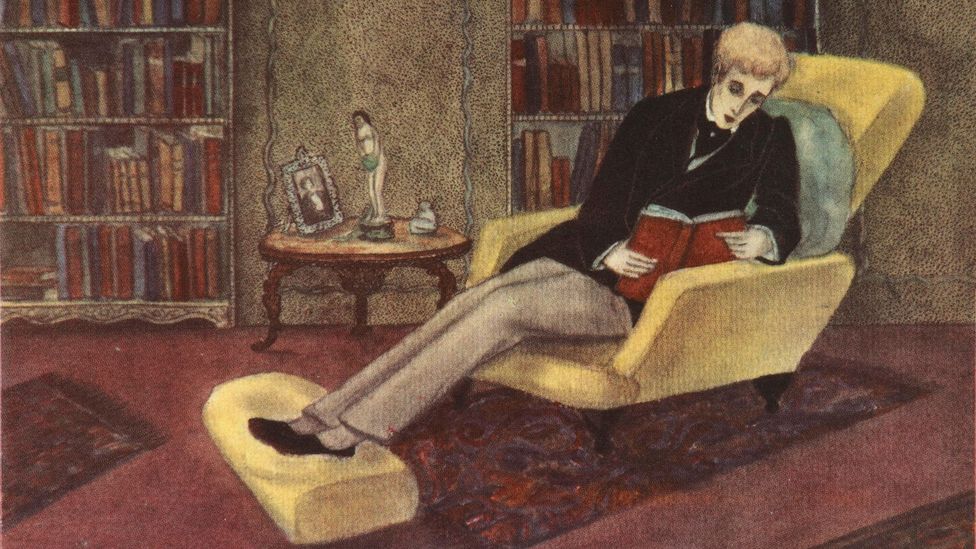

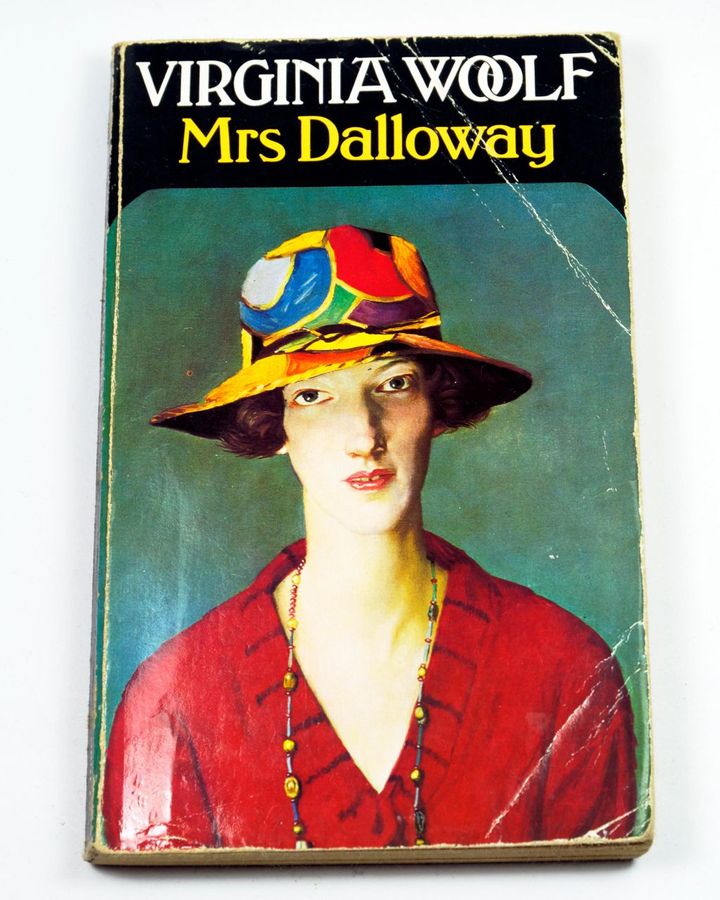

Seemingly small changes can make an enormous difference but as novelists write their way into stories, they sometimes find themselves radically rethinking plots. When Virginia Woolf first conceived Mrs Dalloway, it was a novel in which the eponymous heroine, a character who’d already appeared in her debut, The Voyage Out, would kill herself. Instead, it’s Septimus Smith, a shell-shocked World War One veteran, who will jump to his death. In the notebooks in which she drafted the novel, she can be seen developing him in a way that seals his fate. Meanwhile, the novel’s title vacillates between the one we know and another, later borrowed by novelist Michael Cunningham for his own novel based on Woolf’s life and works: The Hours.

According to the poet Philip Larkin, the literary manuscript holds ‘magical’ and ‘meaningful’ value

In a detail sure to set every graphophile’s pulse racing, Woolf wrote in purple ink. She ruled her own margins in blue pencil and used them not just for insertions but also to tot up her word count, a very practical way of cheering herself on. There are diary-like confidences, too: “a delicious idea comes to me that I will write anything I want to write”, she declares at the top of one page, in bracing contrast to the self-doubts that were simultaneously besetting her. As she told her diary on the day she reached the 100th page of her draft: “It may be too stiff, too glittering and tinselly”. Still, she continues writing and revising until, less than a year later, in 1924, she’s changed her view. “There I am now – at last at the party… Now I do think this might be the best of my endings.” The novel was published in 1925.

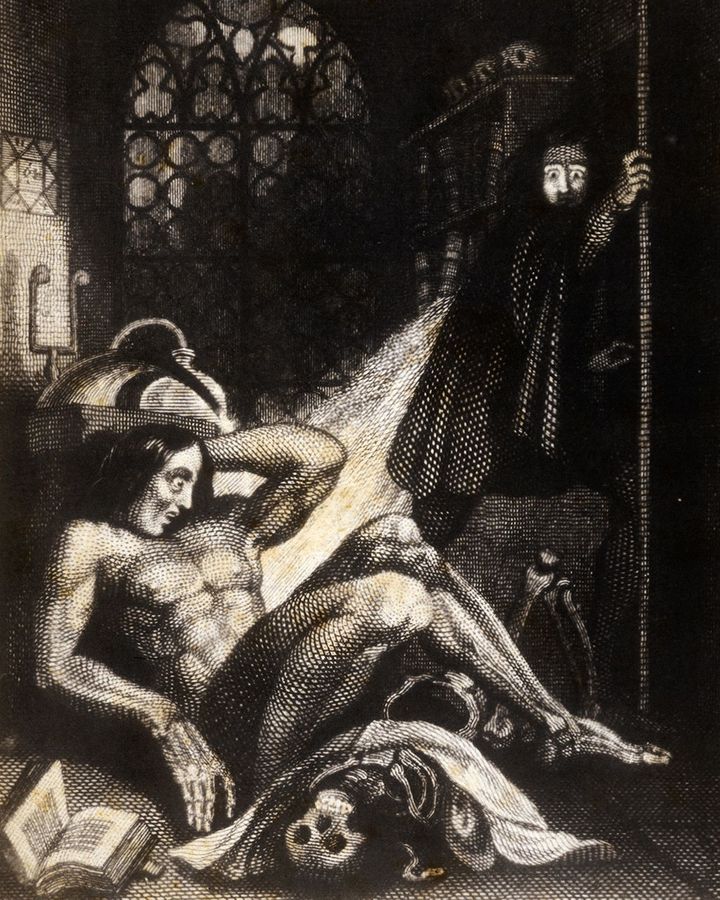

Magic and meaning

When Frankenstein first appeared in print in 1818, anonymously but with a preface by Percy Bysshe Shelley, plenty of readers assumed that the poet was its author. In Mary Shelley’s introduction to the 1831 edition, she wrote that people had asked her “how a young girl, came to think of, and to dilate upon, so very hideous an idea?” In keeping with the story’s eerie origins – the stormy nights and sunless summer days beside Lake Geneva – she put it down to a kind of visitation, the result of “imagination, unbidden, possessed”. Yet as the manuscript reveals, inky-fingered graft played a big role in allowing the doctor’s monster to evolve into the more tragic, nuanced creature that’s haunted our imaginations ever since. In fact, “creature”, Mary’s initial description, is later replaced by “being”, a being who becomes still more uncannily human thanks to other tweaks such as replacing the “fangs” that Victor imagines in his feverish delirium with “fingers” grasping at his neck.

The first draft of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein shows how the figure of the ‘creature’ evolved in the author’s imagination (Credit: Getty Images)

Sadly, the refusal to believe that a woman barely out of girlhood could possibly have authored this transcendent Promethean fable has never quite gone away, and Percy’s notes on the manuscript have been used to bolster the theory that he at least co-authored Mary’s novel. While he’s certainly an astute line editor, the chief revelation here is domestic: the radical Romantic was a supportive, affectionate partner. Correcting her spelling of “enigmatic” (in keeping with her propensity for doubling up the letter “m”, the home-schooled teen wrote “igmmatic” – Percy’s own misspellings tended to muddle the “i before e” rule), he adds a fond and flirty “O you pretty pecksie!”. He, meanwhile, is her “Elf”.

This, surely, is as close to being inside an author’s head as it’s possible to get

In The Art of Fiction, Dorothy Parker says “I would write a book, or a short story, at least three times – once to understand it, the second time to improve the prose, and a third to compel it to say what it still must say.” But the world isn’t receptive to all messages, as Oscar Wilde knew. The Picture of Dorian Gray, his best-known work, began life as a short story, and as the manuscript shows, his changes incorporated a degree of self-censoring. References to Basil Hallward’s relationship with Dorian are toned down. Basil talks of Dorian’s “good looks” instead of his “beauty”, while his “passion” becomes “feeling”.

Other passages are crossed out entirely, among them Basil’s confession that “the world becomes young to me when I hold [Dorian’s] hand.” Wilde’s editor, James Stoddart, censored it further but its publication in the July 1890 issue of Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine still caused uproar. Critics slammed it for being everything from plain “nasty” to “heavy with mephitic odours of moral spiritual putrefaction”, and the bookseller WH Smith refused to stock the magazine.

An early manuscript of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray reveals the author’s self-censorship (Credit: Alamy)

Wilde’s notebook drafts, along with those of Shelley, Woolf and Proust, all feature on the backlist of an innovative small press seeking to preserve the visual, tactile encounter provided by early drafts. Founded in Paris in 2012, SP Books publishes limited facsimile editions of literary manuscripts. Large format and assembled by hand, each book is beautiful, from its gilded slipcase to its heavy paper. As SP co-founder Jessica Nelson tells BBC Culture: “In the context of an increasingly digitised world, our goal is to restore the magic of writing as a potent vehicle between the artist and his or her work. We feel strongly about the importance for today’s reader to be able to connect with the author’s hand and delve directly into the manuscript”. It comes at a price, of course: these collectibles are not cheap.

The original notebooks and manuscripts are mostly locked away in libraries and academic archives, where access is by necessity strictly regulated. It hasn’t always been this way, though. A couple of centuries ago, such veneration would have seemed bizarre. There’s a danger to fetishising these relics and their analogue authenticity: literature’s real vitality, let’s not forget, lies in its ability to fly off the page, and books ultimately belong to their readers. Even so, it’s hard to resist the dynamism of pages from a manuscript like Vladimir Nabakov’s first draft of Invitation to a Beheading, complete with curling arrows and asterisks. This, surely, is as close to being inside an author’s head as it’s possible to get. Pages from early drafts of Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead convey a similarly vivid impression.

Virginia Woolf radically re-thought the plot of Mrs Dalloway while writing the book (Credit: Alamy)

Robinson, along with the likes of Paul Auster and Martin Amis, is one of a dwindling number of authors who still draft in longhand. The poet Philip Larkin told the Paris Review that the literary manuscript holds ‘magical’ and ‘meaningful’ value, and penmanship seems vital to the former. Whether it’s Kafka’s herky-jerky script, pulsing with eccentric energy, or George Eliot’s, which seems to exude a confidence she rarely felt off the page, handwriting conveys something of an author’s state of mind in a way that ‘track changes’ simply can’t.

Then again, it also presents its own challenges. Sometimes, a manuscript’s chief contribution to literary scholarship lies in straightening out typographic errors previously introduced by an author’s hasty scrawl. In one noted episode, laurelled Harvard scholar F O Matthiessen hung a discussion about discordant harmony in the work of Herman Melville on the phrase “soiled fish of the sea”, which crops up in White Jacket, Melville’s fifth book. As it turned out, the adjective was “coiled”, and the author was merely describing eels.

https://ychef.files.bbci.co.uk/976x549/p08wg83j.jpg

0 Comments:

Post a Comment